This is one in a series of posts detailing my participation in a clinical trial with an artificial pancreas element. I’m writing about this to chronicle my experience, and because if I were reading, I’d want to know about every aspect of what was going on. For more on this clinical trial, click here.

Last week, we reached the first admission for the clinical trial I’m participating in. This trial includes time hooked up to an artificial pancreas system. The AP system and the algorithm running on it was designed at University of California Santa Barbara, and is being tested there as well as at University of Virginia and the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota. As much as I can, I’m going to give you the play-by-play of everything that occurred over 48 hours or so from May 27th through May 29th.

The first thing I had to do was insert two Dexcom CGM sensors two days ahead of the admission. We needed to make sure there was enough time for the sensors to get calibrated, and for all of us to make sure things were working properly. There were two sensors because we needed one to work with the artificial pancreas system we were testing, and one as a backup, just in case. For the record, during the day and a half of closed loop testing, I had 2 Dexcom sensors and 2 infusion sets (one for the pump used in the trial, and one for my own) inserted around my midsection.

Then I had to actually get there. That meant driving to Charlottesville Tuesday night, so I had time for my BG to calm down before the admission officially began on Wednesday around noon. I could have gone down on Wednesday morning, but the concern for me was that among the many guidelines (read: rules) in this study, I couldn’t be admitted if my BG was 250 mg/dL or over. My glucose level really spikes after I drive anything over two hours. Since Charlottesville is about four hours away, I went down on Tuesday night.

This admission (and next week’s too) took place at the research house that the Center for Diabetes Technology has in Charlottesville. It’s close to the university and the hospital, but a lot less clinical, and that’s nice. Anyway, after a comfortable night’s sleep and breakfast the next morning, I gathered with the other participant in this trial and the staff working on the first part of this admission.

We began with a BG check, then lunch. What a great way to start! About the meals: We could eat anything we wanted, including snacks, as long as they were under 90 grams of carbohydrates. The thing is, however: Anything we ate at last week’s admission (with the exception of potential hypo treatments), we have to eat during this week’s admission. Exactly. At the same time.

After lunch, the teams started the process of getting us hooked up to the closed loop system. We had to bring our own insulin, and it’s used in an Animas Ping pump for this trial. Good for me, since I’m still thinking about a pump change, and I hadn’t used a Ping before. Once we were hooked up to the pump, and I disconnected my personal pump, we went into another room while more team members completed the rest of the steps to get the closed loop system started. There are a number of detailed steps in the process. So many that a written “sequence of events” is followed.

All went well, and I was introduced to everything I needed to have in close proximity to me for the rest of my time there. This included a tablet that the artificial pancreas system ran on the entire time. But it also included:

– Insulin pump (of course)

– Receivers for the two Dexcom sensors

– My OneTouch Ultra2 meter to be used in the study

– Since it’s a Ping pump, it included the meter remote that’s usually used in conjunction with the pump. In this case, the meter remote was getting data directly from one of the Dexcom units, then sending the data to the AP algorithm loaded to the tablet. That algorithm was designed to take that data and use it to give micro boluses every five minutes during the trial. For this part of the trial, for me, something between .05 and .25 units at a time. Are you still with me?

– A phone. The idea of this phone was to be able to receive messages when my BGs could possibly get dangerously out of range.

I should tell you that the tablet had one of the Dexcom receivers (the non-backup) attached to it with velcro, and the meter remote was attached with velcro to the back. Here’s a shot of everything working together:

Still, that’s a lot to carry around. Imagine having all of that with you, and having to have it in close proximity to you all the time. Including in the kitchen, in the shower,etc. I had a bit of exercise both days, and that meant someone on the team had to be with me with the tablet close enough to me to read the Dexcom and send insulin via remote. It was working right next to me while I participated in the Wednesday night DSMA Twitter chat.

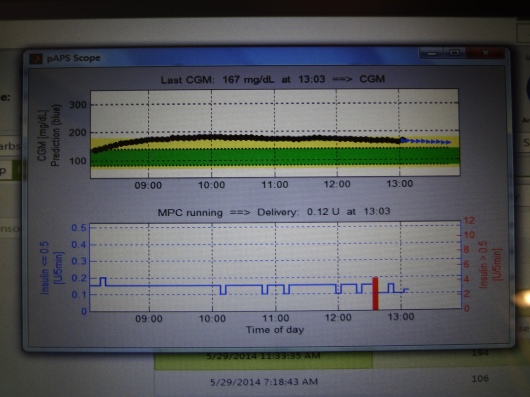

Here’s what one of the screens looked like. The top number is my BG readings from the Dexcom sensor (the black part of the line are actual readings, and the blue part is predicted readings), and the bottom graph is the amount of insulin being doled out every five minutes during the same time. The red vertical bar in the insulin graph marks my bolus from lunch.

As you might imagine, there were regular fingerstick BG tests throughout the admission. And every 15 minutes, night and day, someone was coming by to check my tablet and write down specific data.

Now, you might be thinking: Hey, this is crazy… Who, in real life, would put up with all of that? To which my answer is: This is a test of a system that is in development. It’s not the ready-to-take-home version of something you’ll be filing insurance paperwork for soon. At this point, I think they just want to see if what they’ve worked on so far is doing what they want.

I also realized that something like this, which in theory eliminates basal rates, requires a complete change in thinking. I can’t quite put it into words yet. I spoke a little with the doctor in charge of this testing, and between us, we understand that comparing the management of my diabetes with an AP system versus what I’m doing now is like comparing apples to artichokes. I came away with a completely different way of looking at my diabetes, and a fresh set of questions about what we need from a fully integrated artificial pancreas system once it’s ready for approval from the FDA. More to come next week!

Comments

Phew! That is overwhelming, but exciting. So thankful you are being open about your experience because your post is so informative. Looking forward to reading more about the study!

LikeLike

Wow, Scott, thank you for sharing this experience in such detail. Looking forward to your future posts. My endo was telling me about the AP trials at today’s appointment and then tonight I read your story. You are brave! Thank you for doing this.

LikeLike

this is awesome!! I really enjoy reading patient experiences with this new AP project. Can’t wait to read more!

LikeLike

Absolutely fascinating. I never thought about the fact that we’ll need to completely change our thinking, but we will!!

LikeLike

Yeah, I’m still thinking about what I want to say about it. But it’s something I didn’t expect when I started this.

LikeLike

And thanks for all of the great comments!!!

LikeLike

Trackbacks

[…] in a clinical study before? Well, if you’re curious what one may be like, here’s the inside scoop from type 1 blogger Stephen […]

LikeLike